Seven Days (part 1)

I was in the hospital for a total of seven days. Three in the Heart ICU and three in a room on the Heart Floor. Here is part one of my meanderings:

7 Days, Part 1

There is no privacy in the ICU. It is essentially a bunch of large cubbies with a curtained fourth wall that is never quite wide enough for full concealment. The cubbies all face a huge desk where the nurses live for 12 hours at a time. You can hear everything in the ICU and know almost everyone’s ailments. I heard men moaning, machines beeping, and nurses chastising patients then gossiping about said patients. I heard terse conversations between family members and saw staff performing CPR.

At first, I wasn’t sure what I was seeing. A nurse kneeling on a stretcher quickly moving up and down, alarms going off, the family crying and watching, and then it hit me, his heart had stopped. I shut my eyes, but I could still hear staff yelling “Hold compressions!” over and over again. I could still hear his family crying and praying. I heard the doctor tell the family the man was sick, and his heart was very weak. They saved him this time but may not be able to save him again. There’s a lot of crying and praying in the ICU. It was an emotionally thick three days. I felt both grief and guilt. At some point, I would leave the ICU. I knew I would go home. Although I wasn’t out of the woods, things were progressing as they should and no one in my life was worried for my life. We had that luxury. Other families did not. This was something I felt deep inside my bones.

Day one was surgery which I wrote about in previous posts.

Day two - the day after surgery - is the worst. All the anesthesia is gone. I imagined it disappearing from my body like water evaporating on hot cement. I was weak, nauseated, and in deep amounts of pain. Sharp, heavy, electric pain pierced my chest and my heart. No matter what the nurse did, she could not get the pain to go away. It was a vast hurt, a deep dark cavern that swallowed everything the nurse threw into it. On the pain scale, we were speeding past seven and going straight to nine. My family was agitated at the nurse, and the nurse was agitated at my family. I said something about not expecting this much pain. The nurse was sympathetic, but there was an edge to her voice. She said, “It's a painful surgery. They cut through muscles, nerves, and tendons, and then they manipulate your ribs, pushing and pulling them. They cut your heart open. You had a device sewn into your heart, and everything is tight and swollen.” She said it as though “Duh, we know you're in pain, so stop asking for meds.” She said she had to try a couple more rounds of morphine, slightly increasing each dosage. If they didn’t work, she would pull out the big guns. Something that started with a D. She said the shot would go in my shoulder, and it would hurt. Pain to relieve pain. I almost laughed. The irony was a bit much.

Here was the source of my agitation: If you know exactly what happened to me, then give me the medicine that is going to take my pain away. Don’t waste time marking off some protocol checklist. LISTEN TO ME! Why make me drown in hurt? And, if you described exactly what happened to me, in great detail, then why must I repeatedly prove my pain to you? You already know I am in great pain, and yet you still give me weak painkillers. Why are you frustrated that I continue to share my distress with you? If I didn’t stand up for myself and voice my pain, how would anyone know I was in pain? Why does it always feel that women must silently endure discomfort of all kinds? Why can’t we voice it without someone thinking we are overreacting? I believe women are built to weather the piercings of pain. Its very edges cling to us in so many physical and physiological ways, and yet we keep going. It's an amazing strength, but it has trapped us in a suffocating expectation of stoic silence. Perhaps real strength lies in admitting there is pain. Women should be given relief without someone, especially another woman, saying, “Well, we need to see how bad it is first.”

At this point, I had been in hot, dark, sharply intense pain for a while. I was trying desperately to escape it. Mentally, I was clawing at the walls of life, banging on reality trying to find a doorway out, desperate for release and relief. Pain can make one feel claustrophobic, frantic, and insane. I wasn’t thrashing about in my bed, but I was shifting, moaning, and doing my best to keep the tears from falling. Then, with sudden clarity, I realized I would be in pain for at least another couple of hours, if not longer. I knew the nurse would follow her protocols. I knew the morphine wasn’t going to work. I knew I would have to wait a while for the nurse to see it wasn’t working. She would then have to place a call to the doctor, the doctor would have to return the call, give his permission for the D stuff, then the meds would have to be called into the hospital pharmacy, then brought up to me. All of these steps laid themselves out perfectly and succinctly in my brain. I had a choice: continue to be driven crazy with pain or accept it. Go into it, stop fighting it, and be present for it. The only way to heal is to go into the pain.

I clearly remember adjusting my shoulders, lowering my head, mentally centering myself, and breathing. I left everything in the ICU behind. I couldn’t talk to anyone, look, listen, or smile. I just went inside my chest, to my heart, and stayed there. I breathed in and out, visualizing oxygen going to my heart. I worked on clearing my mind, practiced box breathing, named things I was thankful for, and then repeated it. It took the edge off the pain. At some point, I was able to bring myself back up and interact in short amounts of time with my family before going back inside myself and sending oxygen to the pain again. I lost track of time.

Miraculously, the nurse came in with the shot of magnificent D-something. Holy hell that shot hurt, but holy hell did it work. From that moment on, I did not hesitate to ask for pain pills before any pain started. I don’t care if the nurses thought I was weak and a wimp. I knew I had just faced my pain and won, but it wasn’t something I needed to continually prove to others. Pain may have its place. It warns us when something is mentally, emotionally, and physically wrong. But damn it, when someone says please help me make the pain stop, then help them make the pain stop.

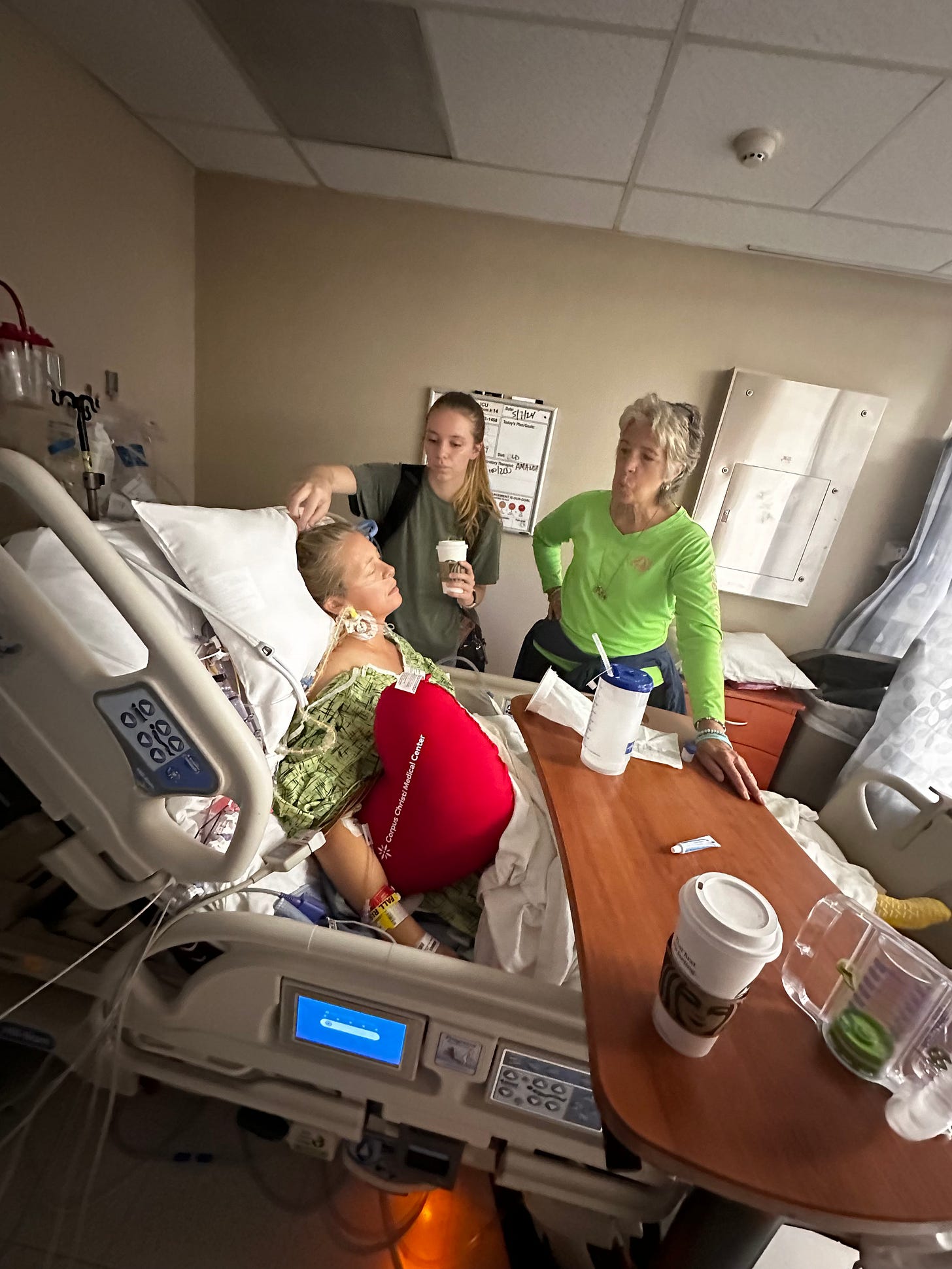

Breathing through the pain with my daughter and mother.

Day two continued to be a long one. Now that the pain was managed, I wanted to face my incision which, over the next several months, would turn into my scar. This scar had already been a part of my body. It lived in my mental illness. It developed from years of eating disorders and self-loathing. Mental scars can only stay hidden for so long before they seep into physicality. Although this scar was brought forth through the incision of my surgery, it had always been in me, waiting to be revealed. The incision went from the center of my chest, along my pectoral muscle, under my right breast. There was no bandaging, just glue. I could see bruising, but I could not see the incision without the aid of a mirror.

I turned to my sister and told her to lift my gown and see what only sisters can feel comfortable seeing. I told her to take a video of my incision. She did what I asked. I didn't allow myself to hesitate, I immediately watched the video. A deep purple storm cloud had formed under my right breast. Threaded through it was a line the color of merlot, the incision. That was where my mental illness burst through my body. I decided it was where anorexia had exited, leaving behind its battle wounds as evidence. Although I framed my thoughts this way, it was still quite disturbing. I don’t remember my exact reaction. Maybe that's for the best. I didn’t look at my incision again until I was home.

I had never heard my heart before the valve replacement, but I am told it sounded squishy. My cardiologist stopped by my ICU cubby that day to check on me. This was after my pain was under control and I had faced the incision. He listened to my heart and said, “That is a nice sound.” Although I could hear the tick of the valve, I had yet to hear my actual heart beating. I told him it was odd how so many people get to see and hear parts of me that I will never get to experience. I wanted to know what he heard: a clear heartbeat. He smiled awkwardly at me and nodded but then turned and left. Has no patient ever expressed that to him before? Doctors and nurses get to see us in ways we do not and it's weird. I will never touch my heart, but a doctor I knew for five minutes has. A whole surgical staff has seen and heard it, but not me.

A few minutes later the nurse came into my cubby. She was cleaning a stethoscope. I still tear up now thinking about her putting it in my ears and her hand guiding it to my heart. I am not sure if the tears are because I got to hear my beautiful, clear heartbeat, or because of her kindness. Either way, it leaves me with gratitude. As night crept into the ICU, I called the nurse over to my bed. I told her that today had been intense. We were all feeling the strains of post-surgery. I thanked her for helping me. She nodded and apologized if she came across as uncaring. She cared. I gave her a tight smile and then she left. I didn’t see her again.

By the morning of day three, I was learning to make peace with the ticking of my new mitral valve. I woke up at night to it ticking, fell asleep to it ticking, and sometimes I purposely got quiet to hear it tick. If I woke up during the night and couldn’t immediately locate it, I would panic, thinking it stopped and I could die. The anxiety of a patient leaves little room for common sense. We are tired, our defenses are down. At night there is no one to talk us off the ledge, so we panic. I would force myself to concentrate on the ticking and hug my heart pillow tight as I breathed. I would remind myself I was safe and in the hospital. Eventually, I would calm myself down, and the night would resume. It would fill itself with moaning, crying, nurse murmurs, beeps, and snoring. It's a very lonely and vulnerable feeling. Thank goodness my husband was there each morning when I woke up. Those first two nights in the ICU, I didn’t remember saying goodnight to him, or him leaving. I asked what time he left the hospital each night and when he returned each morning. He looked at me funny and said, “I’m not going home, I am sleeping on the couch in the waiting room.”

Yeah, he’s that kind of guy.

There was a night nurse that was so gentle with me. Before she left in the mornings, she would wipe me down with baby wipes and bring me a cup of coffee and a toothbrush. I am forever thankful for those little blessings. The “bed bath” was refreshing. Each wipe erased a layer of pain, discomfort, and frustration, along with this perpetual orange disinfectant that was all over the front of my body that started getting gross and sticky after day two.

Day three came with the removal of the catheter and the wires jutting out from my neck. I welcomed the arrival of a mobile potty chair, a new ICU room, the ICU’s version of a Lazy Boy, and learned the true purpose of the Heart Pillow. Part of recovery requires sitting in a chair for at least an hour. I looked at the chair and the two nurses there to move me into it. I was at a loss as to how to get from the bed to the chair. They instructed me to wrap my arms around my heart pillow, squeeze, and listen to their instructions. I wanted to do exactly as I was told because I needed them to know I was a good and dutiful patient. However, as soon as I was settled in that chair, I started coughing uncontrollably. Holy hell, I thought my chest was going to split open along the incision. It was a sharp electric pain that sizzled left to right and back again on the inside of my incision. The only way through pain is to face it. I concentrated on it, breathed oxygen into it, and squeezed the life out of that pillow.

Halfway through the day, they moved me, via Lazy Boy, to the furthest room in the ICU, away from the nurses’ desk. This was a room that came with a sink, a fourth wall, and a door! It was a luxury. Mom stayed with me that night so my husband could go home and get some sleep. Of course, because my catheter was gone, Mom was responsible for once again helping her daughter sit on a potty chair...much like she had to do when I was two, except now I was 48.

The chair was in the middle of the room. I would call the nurse, who had to come because I still had a chest tube connecting me to a white plastic box with a clear front. It collected the blood-tinged fluid that built up in my chest after surgery. Her job was to make sure my chest tube did not get pulled out. Mom helped me shuffle to the adult-sized potty chair, where I would sit and, well, “go” in front of both nurse and mother. Because I was full of all kinds of liquid, I would go for a comically long time. It was beyond embarrassing, but also slightly funny. There is no room for modesty or ego in the ICU. You have to laugh or cry. If I have the option to pick my emotions, I’m going for laughter every time.

Day three ended with my first cardiac rehab session. I had to walk..er..shuffle.. around the ICU. The therapist held me steady as I gingerly walked around the nurses’ desk. It was like a field trip. I got to see the rest of my fellow patients in the ICU. I passed the man who had been resuscitated on day two, his family was praying outside of his cubby, older couples sat silently in dimly lit spaces watching me shuffle past, and others softly moaned in pain or slept. Nurses carefully brushed past me doling out meds, answering calls, and managing other people’s discomfort. I was the youngest in the ICU by at least 20 years. Halfway through I dropped my eyes and concentrated on squeezing my heart pillow and putting one foot in front of the other. Tomorrow, I will be moved up to the Heart Floor. One step closer to going home. I wondered when my fellow ICU-ers would get to head up to the fourth floor too. I’ve stated before, I am an empath. I can feel other’s emotions. Walking around that ICU was so heavy. It was too much. I went back to my room and shut the door, I was not going back out there until it was time to leave. I may be able to face my pain, but I could not face the hurt of others.

Searingly tender